"APPLIED HOPE"--TIME FOR A REVIEW OF WHAT COULD AND SHOULD BE DONE

The Interview with Amory Lovins, the World's Most Pragmatic Climate Visionary

With the all the backtracking on climate and health by the Trump Administration, frying the earth and letting the grandchildren sicken and suffer along the way, I thought it might be exhilarating—for a change—to re-print what we could and should be doing in America and as humans in a changing and perilous time. Hence reprinting here one of the most popular HOT GLOBE columns of the last few years:

Transcript to the Hot Globe Interview with Amory Lovins, the World's Most Pragmatic Climate Visionary:

"Applied Hope”

First, thanks to so many Hot Globe free- and new subscribers for Upgrading to Paid with our end of 2023 appeal, “It’s a Wild and Wonderful World.” That’s what makes Hot Globe’s unusual interviews and climate analysis possible. Here’s a chance to start the New Year feeling good:

Next week we return to Lahaina, Maui, Hawaii, for an optimistic message for the new year from the brilliant, encyclopedic and irrepressible official archeologist of the Island, Dr. Janet Six.

But many of you wanted to read the transcript of our talk with Amory Lovins, co-founder of the Rocky Mountain Institute and a climate visionary whose ideas are now widely adopted throughout the world. If you want to change the future, it is pretty much helpful to check in with Lovins first. So here’s the transcript. (I mean, who has time to view a 30 minute video, unless it’s Succession or White Lotus!)

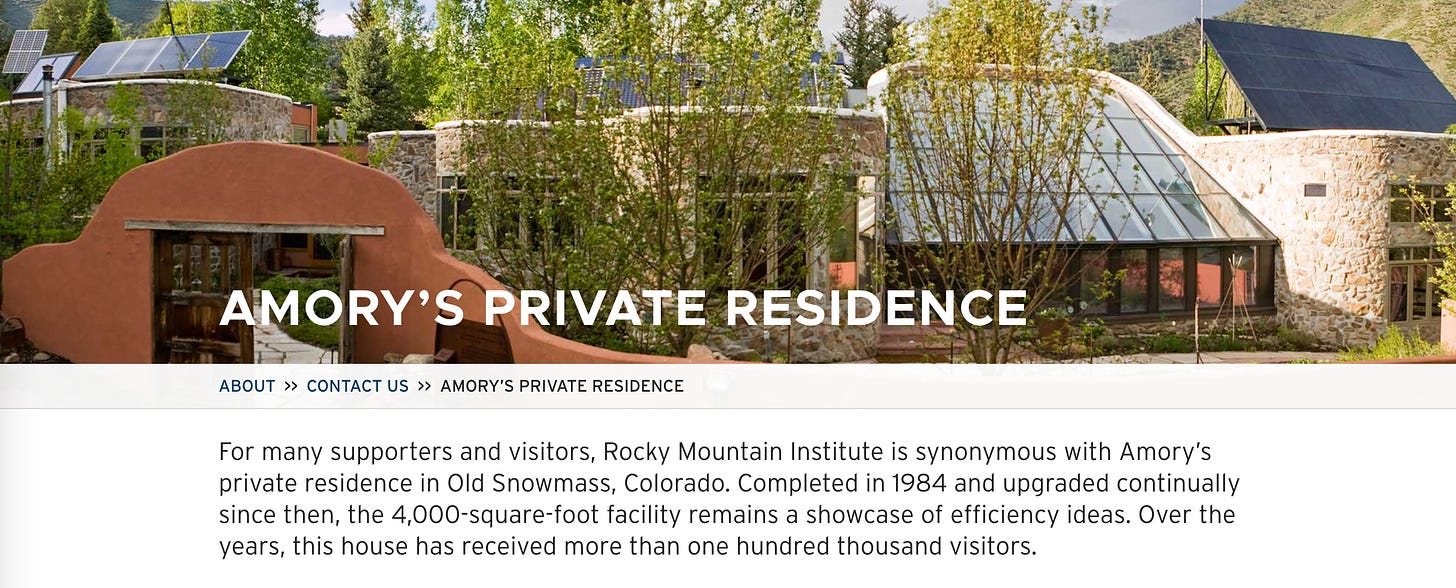

Amory Lovins in his “radically efficient” house in Old Snowmass, Colorado, 2200m feet up, where this winter he enjoyed his 42nd consecutive crop of bananas in the enclosed solarium behind him.

HOT GLOBE: Hot Globe here with Amory Lovins. I'm going to say the legendary Amory Lovins, co-founder of the Rocky Mountain Institute, energy consultant to corporations, states and governments, author of Soft Energy Paths, Natural Capitalism with Hunter Lovins and Paul Hawken, and most recently, Reinventing Fire. Amory pretty much invented the energy efficiency revolution.

Amory, to address the climate crisis and decarbonize the world, people talk endlessly about solar, wind, batteries, better grid, but you say saved energy is the world's biggest energy source today.

AMORY LOVINS: Oh, yeah. It's a lot bigger than oil. Of course, the renewables revolution is extraordinary and wonderful. But let's not forget that efficient use is about half the historic decarbonization in the world and at least half of the prospective decarbonization. So we shouldn't forget about the demand side of using all forms of energy efficiently and in a timely fashion. That's generally the cheapest, fastest thing to do. It has its own set of barriers. There’s 60 or 80 obstacles to using energy in a way that saves money, but each one can be turned into a business opportunity.

HOT GLOBE: You've gone from the soft path—energy efficiency, renewables--which was a great concept adopted by the entire world but now you’re ramping it up with the concept of radical energy efficiency--

AMORY LOVINS: Oh, I've been doing radical energy efficiency for about a half century, but particularly now that we figured out and demonstrated it as whole systems for multiple benefits, not as isolated little parts for single benefits. People are starting to realize pretty widely you can do that with buildings, but it turns out you could do the same thing with factories, equipment, vehicles, anything that uses energy and resources. This turns out to make the whole energy efficiency resource several times bigger, but also cheaper and often with increasing returns, just like renewables. That is, the more you buy, the cheaper it gets. So you buy more, so it gets cheaper.

HOT GLOBE: Why haven't we moved on that part of the equation as much? Is it less sexy, not so much ribbon-cutting for the politicians?

AMORY LOVINS: For starters, the only place I know it's taught is by Joel Swisher and me at Stanford. It's not in any standard engineering textbook. It's not in any government forecast or industry forecast or any climate model. So naturally, it hasn't spread nearly as far or fast as it could. And actually, it could probably be spread, I suspect, by images and memes through social media. You don't have to go back to school and learn a bunch of new theory. If you just see how it's done, it becomes obvious. Let me give you a few good examples of how this works. Let's start with what you can see behind me. I'm talking from our passive solar banana farm home and office 2200m up in the Rocky Mountains near Aspen, where it used to go to -44 C, -47 F on occasion. It doesn't anymore, thanks to global weirding, but it's still gets awfully cold here. And we've seen 39 days of continuous midwinter clouds. But banana crop #41 is ripening behind me in a jungle with 100 odd kinds of other tropical plants. And by the way, there's no heating system, and it was cheaper to build. The reason it's cheaper to build is that you save more on construction costs, leaving out the heating system.

Then you pay extra for the super windows, super insulation, ventilation, heat recovery, all the stuff that gets rid of the heating system. In other words, we're optimizing the building as a system, not the installation as a component. The more you add the cost goes up and most people get stuck on that diminishing returns curve that we learn about in business school and forget that if you save enough, you make the insulation several times better than normal, suddenly you don't need the furnace ducts, fans, pipes, pumps, wires, controls, fuel supply arrangements. So the total construction cost goes down to less than you started with. And why should you get there the long way around, when you can tunnel through the cost barrier by asking upfront? Is there some sensible way to design this building so it won't need heating or cooling? It turns out this works from our climate to say Bangkok. That range spans essentially everyone on Earth. So that's encouraging, and you could also retrofit pretty much this level of performance cost effectively. So that's a building example. Okay so far?

Now out in the driveway is my BMW i3 electric car made of carbon fiber, which is very light and strong. That was thought to be hopelessly expensive because they looked at cost per pound, not cost per car, which is how I buy cars. Well, it turns out that two thirds of the energy needed to move a car is caused by its weight, and the rest is air drag and the rolling resistance that heats the tires and road. So it would really be nice to start by saving weight, but instead of just looking at how much does the carbon fiber cost compared to the same weight of steel, you need to think about how in an electric car, the most expensive thing is the batteries. So the lighter and more slippery the car is, the fewer batteries you need for the same range. Right? And that takes out cost that then pays for the carbon fiber. That was true even of the much higher carbon fiber prices of over a decade ago, and BMW profitably sold a quarter million such vehicles. And by the way, the manufacturing, as we had claimed and been ridiculed for, is also radically simplified. It turns out making that car takes a third the normal water and capital investment and half the normal energy, space, and time.

HOT GLOBE: I should say that you basically came up with the concept of the HYPERCAR and certainly popularized it, which was a big deal and a great name.

AMORY LOVINS: Now stolen and misused by some other folks who--yeah. I'm not too hung up on the name, but the concept is if you make the car 2 or 3 times more efficient by taking out weight and drag and rolling resistance and accessory load, , then you need a much smaller propulsion system to run it. And as that gets smaller and cheaper, it's much easier to electrify it, which then boosts efficiency further. So you end up with a factor, roughly 4 to 8 efficiency gain on cars by combining efficiency and electrification. And that that combination can save enormous amounts of, of not just electricity, but also recharging infrastructure, and investment. It's a very lucrative thing to do. And you can apply it to all kinds of vehicles. Okay. So that's a vehicle example okay. This is not such complicated stuff.

So let's try another example. If we were to go in our utility room you would see some pipes we put in to circulate surplus solar hot water to replace what? We used to have a couple of wood stoves, for the last 1% of our space heating and our master plumber said, okay, you got all this hot water sitting in this big tank and you need to circulate it to the floor slabs you put in in ‘83, in case you might ever need them. How would we circulate? Okay. It's easy. I'll get you a big primary pump and six smaller zonal secondary pumps. I said, well, that's kind of a lot of pumps. Don't they use a lot of power? He said, oh no, it's trivial, 2.3kw. I said, that's way over twice what the whole building uses for everything. Let's talk about low friction pipe layout. So I showed him how to make the pipes fat, short and straight instead of skinny, long and crooked. Right? And that saved 97% of the pumping power.

HOT GLOBE: It's all called integrated design.

AMORY LOVINS: So we ended up with, with a 43 watt max pump, one of them instead of seven pumps totaling 2300 odd watts. So of course it was cheaper to build. It turns out if everybody in the world did this, it could save a fifth of the world's electricity or half the coal fired electricity, and you typically get your money back in less than a year on retrofit and instantly a new construction. So that's a big deal. And by the way, that means that your motor systems also get 5 or 10 times smaller. So you can then scrap them, make much more efficient new ones. And then the savings rise to about potentially a third of, world electricity use.

HOT GLOBE: Strong statement.

AMORY LOVINS: The energy transformation now underway is the biggest technology shift since the invention of agriculture. Yep. We're holding to that.

And that we all stream and downstream, is what makes that possible or could make it possible.

Of course, the more efficient you get, the more fossil fuel you will save for the same amount of renewables because you're squeezing out the fossil fuels from both sides, going down through efficiency and clean supply, coming up from renewables.

And that means that the transition gets easier, cheaper and especially faster, which is a really good thing, that's why I hope people will start paying a lot more attention to efficiency. The, the recent COP declaration that let’s triple renewables and double efficiency is not trivial. It has certain challenges, but it's certainly feasible. But I think we can do a lot better than double efficiency. And in fact, the International Energy Agency has a big group of countries that have agreed to double the speed of saving energy from 2 to 4% a year. I think we can do even more than that, but that would be very helpful.

HOT GLOBE: Talking to some of our younger audience here at Hot Globe who might be, you know, reaching for the Prozac at some point— you've come up with a concept applied hope as well, that not only is not all lost, but it shouldn't be lost. And the optimism is maybe a little bit of a of a naked, foolhardy way to go. You need applied hope. You need to make things happen. Is that about right?

AMORY LOVINS: Yeah, Dave Brower said that optimism and pessimism are different sides of the same coin, simplistic surrender to fatalism, where you treat the future as fate, not choice. And don't take responsibility for creating the world you want. Right? So I

I'm not an optimist or a pessimist. I live and strive in applied hope, , which is not just theoretical hope or mere glandular optimism, but it's making sure that what I do every day is helping create a world worth being hopeful about. And, , you know, as Frances Moore Lappe says, hope is a stance, not an assessment. There's a great Welsh development economist who once said that to be truly radical is to make hope possible. . .

HOT GLOBE: Can we do all this in time to avoid climate disaster, do you think?

AMORY LOVINS: Well, I think Dana meadows got it right when she said we have exactly enough time. Starting now.

HOT GLOBE: Okay, some potential pushbacks. You've said that the war in Ukraine will hasten the energy transition in Europe.

AMORY LOVINS: Already has enormously.

HOT GLOBE: Okay. Is that already happening, by the way?

AMORY LOVINS: Oh, very, very much so. Because

Putin made it clear that energy security was back on the agenda and so was energy. Huge energy price volatility, which buffets economies right down to your wallet, and he, therefore, has blown up the fossil fuel era, the basis of his own power, faster than would otherwise have occurred.

Okay. So what Europe did was to double down on speeding efficiency and renewables, both of which are highly secure, constant price, you know, stable price, reliable supplies and the US then joined in with the Investment Reduction Act and other such legislation and, some other parts of the world are starting to come on board.

So I think if we really continue to pursue that fast energy transition that Putin accelerated, with the focus and resolve that especially Europe has displayed, then Ukraine's agony will not have been wholly in vain.

HOT GLOBE: What about the worry that many people have about the new big LNG plants on the Gulf Coast? As of a few years ago, America has been allowed to export fossil gas (and oil,) but these huge plants may have the effect of releasing a great deal of methane in their overall cycle. McKibben, for instance, worries about that greatly. What do you think?

AMORY LOVINS: Well, Bill McKibben is right about that, and I say that having helped design some such plants in several parts of the world. But I think there are two other issues with them. One is that if they have an accident or are attacked or sabotaged, each one can be a megaton range ground level firestorm. They can incinerate people and everything else over a very long range. I wouldn't want to have one anywhere near a populated area. And then the third issue, which I think kind of disposes of the other two, is that I think we're way overestimating the need for those gas exports.

And meanwhile, of course, our government has been pushing gas for many, many years onto countries in our hemisphere and elsewhere in order to boost an export. But, I don't think there's a good business case when you compare with efficiency and renewables.

Therefore, if we look at all ways to provide the stuff we want - services like hot showers and cold beer - we will find that LNG is a very expensive way to do those things and we're just throwing a lot of money away along with climate and security.

HOT GLOBE: So it's a question of competing industries, perhaps, or values or entrenched industries.

AMORY LOVINS: All of the above. Of course, when we export that much gas, we are raising gas prices for American users. So we're not getting the full benefit many were hoping for from supposedly cheap fracked gas, which is not really cheap but that's a whole other conversation. Again if you if you use energy in a way that saves money, fossil fuel including gas goes down. I used to think that that gas use would decline decades after oil use. But I think they'll be much more in phase, because if you look at every sector in which we use gas, it's under severe competitive threat that the industry doesn't like to acknowledge. And, you know, friends of mine have reported speaking to audiences of senior executives of the natural gas industry and shown them real numbers for the cost of competing renewables and efficiency, and been told, “those aren't real numbers. You're making those up.”

HOT GLOBE: Denial creeps in.

AMORY LOVINS: You know, I've worked with the hydrocarbon industries off and on for 50 odd years now, and, it's amazing how hermetic that world can be. If you only talk to other people in that industry, you might not realize how you're being overtaken by events.

HOT GLOBE: Okay. Major nations at COP also pledged to triple money on nuclear, I believe, by 2050. Bill Gates and others are pushing small modular reactors known as SMRs. Is that money or madness or what's going on behind the scenes and basically what is your take on nuclear? I know you've written much on it.

AMORY LOVINS: We're in the middle of a very adept and effective PR campaign, which has fooled a lot of people that should have known better. There is no operational need and no business case for nuclear power using any technology and any fuel cycle, and it is in global decline Hannah Ritchie . You may have noticed, by the way, the two countries driving conventional nuclear construction are Russia and China, and they were not part of that statement. It's really about ginning up competition for them in a market that is essentially all sales to or paid for by governments because private buyers of electricity realize it's way too expensive and not very reliable in delivering what it promises. There are, of course, other concerns about it, of which I would put the spread of nuclear weapons at the top of the list. But, since there's no business case for it, it kind of falls at the first hurdle. We just saw with the failure of the flagship SMR project, the beginning of a rather abrupt decline as people realized that this was just a shiny object with a good sales pitch. What they might not realize yet, though, is that nuclear power is one of the main distractions from climate protection and actually makes climate change worse for a very simple reason: it's many times costlier per kilowatt hour than efficiency and renewables to do the same thing. Because it's costlier, that means you get less of it per dollar. Therefore, you displace many times less fossil fuel per dollar than if you bought the cheaper stuff instead.

A rendering, only, of the first NuScale nuclear plant which went bust last month in Idaho. “We're in the middle of a very adept and effective PR campaign, which has fooled a lot of people that should have known better. There is no operational .need and no business case for nuclear power using any technology and any fuel cycle, and it is in global decline” —Amory Lovins

Sustain What That's why it makes climate change worse. It's a rather simple argument about what economists call opportunity cost, which is a fancy way to say you can't spend the same dollar on two different things at the same time, but I think a lot of people haven't quite picked up on this yet because they, they think, “oh, nuclear is essentially carbon free by some metrics” and therefore, it must be a good thing. Well, actually, the more you worry about climate change, the more important it is to count not just carbon, but also cost and speed. All three matter, and if you buy something that's carbon free but slow and costly instead of being fast and cheap and if it's also speculative rather than certain, you're making the climate problem worse in three ways, and you shouldn't make it worse in any way.

HOT GLOBE: Okay. Well, you know, Amory, it's exciting times. There's some scary stuff out there, obviously, but are you kind of excited by much of what you've brought to the world? I mean, to sort of see it begin?

AMORY LOVINS: Yeah! All our wonderful colleagues over the years, over 1000 just at Rocky Mountain Institute. And actually it has 750 staff now and of course, many other colleagues all over the world. I've worked in 70 odd countries. It is wonderful to see this finally catching on. In another three years, it'll be time to do a 50 year retrospective on my old Foreign Affairs paper in ‘76, The Path Not Taken “Energy Strategy: The Road Not Taken”

HOT GLOBE: Everybody should read that.

AMORY LOVINS: It wears pretty well, thank you, and so does our ‘99 book with Paul Hawken, Natural Capitalism.

HOT GLOBE: Exactly. You mentioned that.

AMORY LOVINS: There's already a 40-year retrospective on the Foreign Affairs piece, but I'm looking forward to the 50 year.

Things are going well. Basically we're on track for the efficiency gains that I've anticipated over the years. The renewable part got delayed several decades by hostile policies, but it's now catching up with the vengeance and to give you a notion of how fast it's going, between September 2022 and October 2023, the authoritative Bloomberg estimates of how much renewable capacity the world would add during 2023 went up by 55% while it's underway, which tells you how this is far outrunning what even the best forecasters could imagine.

HOT GLOBE: Well Excellent! You know, I think it must be those bananas back there, all that potassium that fuels what Dina Cappiello christened “Amory’s Brain!” For Hot Globe readers I recommend every book you’ve written and also, right now, the recent opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal by the current CEO of Rocky Mountain Institute, Jon Creyts titled “As the Planet Heated Up in 2023, Clean Energy Took Off.” I think the truth of the transition may have shaken up some WSJ readers, though not the smarter investors! Anyway, thanks so much for talking. Anything we missed here?

AMORY LOVINS: Oh, a lot, but that's just another conversation. Thank you Steve.