Trump Moves to Deny the Evidence of Climate Change

DR. RALPH KEELING SPEAKS TO ATTACKS ON NOAA AND THE IMPORTANCE OF THE KEELING CURVE

"Realistically, we're heading towards about 3 degrees C now."

“Turn the headlights off and we're driving blind.”

HOT GLOBE: Is this magnificent measurement apparatus resulting in the Keeling Curve in any danger from the current administration?

KEELING: Well, there's certainly threats on the horizon.

And so how real they are is hard to say at this point. There was an issue involving the Hilo office of the Mauna Loa Observatory having its lease not renewed. That's a kind of minor issue. If the funding were still there, they could move to another office. So that got a lot of press attention. It doesn't necessarily pose an existential threat if nothing else went on, because one could work around it. It's important to point out that the observatory is run by my colleagues at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. So the operational details are maintained by them. We here at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography collaborate with them to get to get measurements with NOAA. With NOAA. Yeah. Some of the work that's done through NOAA is contracted to universities, through various cooperative institutes. That funding could be threatened by the need to get approval at a political level. We saw an example of that last week with grants to Princeton University and the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Lab Collaborative there that got that got basically denied, presumably because they have some dimension that has to do with climate. So some of the work we do here at Scripps comes through a similar collaborative institute.

THE FULL INTERVIEW HERE. PLEASE READ.

HOT GLOBE: Hot Globe here with Doctor Ralph Keeling, curator of the Keeling Curve at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in sunny La Jolla, California. Very briefly, Ralph, what is the Keeling curve and why has it been called one of the most significant scientific projects or discoveries of the 20th century and the 21st century, too? [Liquidity Note: I was a Visiting Scholar at Scripps, with an office down the hall from Keeling’s.]

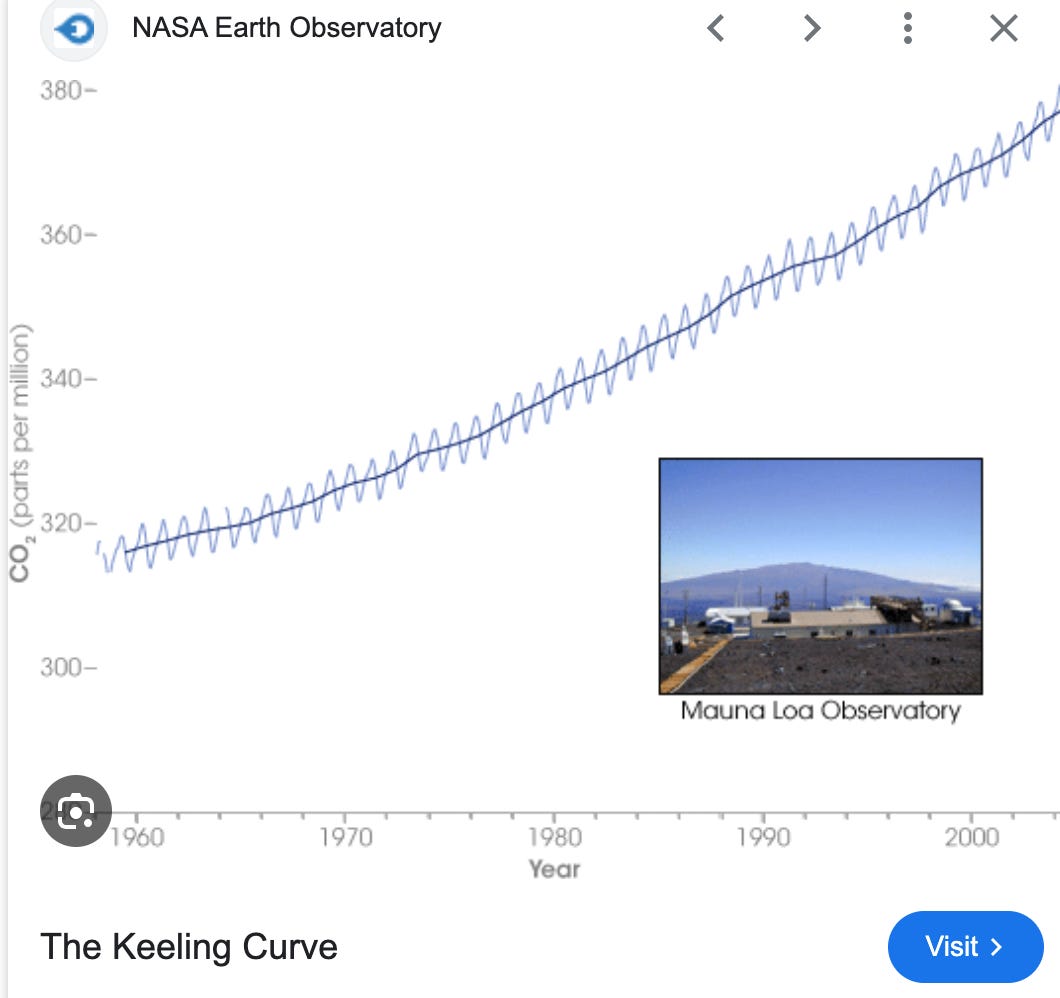

KEELING: Well, thanks, Steve. Of course, I'm happy to be here. So the Keeling Curve is a record of rising carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. It was started in 1958 by my father, Dave Keeling. Um, and it, uh, it's it's the location is significant because it's in the middle of the Pacific Ocean on a way up on the volcano. It's very remote from forests and cities, and it produces a very pristine record of changes in atmosphere, carbon dioxide. It has a it's showing a rise over time, but it also has a seasonal cycle which is showing the breathing of the Earth. It's a kind of a nice indication that we're we live on a planet with life. Um, but it also, uh, it very quickly, even in the first few years, showed a build up of CO2, and it was the first really good evidence that humans were having an impact on the global atmosphere in a way that could affect global climate. And to this day, it remains kind of an inspiration for people. Look at this curve and say, wow, something big is happening. Um, I at least have to know about this. And many people looked at this curve and decided it was inspiration for them to move into this field.

KEELING: Um, so there are scientists who are modeling climate impacts of CO2 looked at this curve and said, wow, this is big. This is a big issue. This is something we ought to be studying. And I guess the record is incredibly detailed. So it's a kind of a beautiful achievement of science in showing so much detail and so much information. Um, but it's also super valuable. I mean, it's it's a it's it's a it's a kind of a bottom line for where we are. If we if we're going to bend the curve, what's the curve? Well, this is the curve. This is the curve we're going to we need to bend right. And uh it also because it's so long, it's also a great record for assessing whether we're on track or whether we're not on track, and whether anything surprising has happened because we have now more than 65 years of of data establishing what natural variability in this rise looks like. We can make forecasts going forward based on this curve better than we could without it.

HOT GLOBE: Is this magnificent measurement apparatus in any danger from the current administration?

KEELING: Well, there's certainly threats on the horizon. And so how real they are is hard to say at this point. There was an issue involving the Hilo office of the Mauna Loa Observatory having its lease not renewed. That's the kind of minor issue. If the funding were still there, they could move to another office. So that got a lot of press attention. It doesn't necessarily pose an existential threat if nothing else went on, because one could work around it. Um, it's important to point out that the observatory is run by my colleagues at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. Um, so the operational details are maintained by them. Uh, we here at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography collaborate with them to get to get measurements with NOAA. With NOAA. Yeah. Some of the work that's done through NOAA is contracted to universities, through various cooperative institutes. That funding could be threatened by the need to get approval at a political level. We saw an example of that last week with grants to Princeton University and the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Lab Collaborative there that got that, got, uh, basically denied, uh, presumably because they have some dimension that has to do with climate.

So some of the work we do here at Scripps comes through a similar collaborative institute. I should point out that in addition to measuring carbon dioxide in my group, we also measure changes in atmospheric oxygen. It turns out oxygen is decreasing in the atmosphere as CO2 is going up. What does that sound like? Well, it sounds like what happens when you have a fire, right? Takes up CO2. It takes up oxygen from the air and makes CO2. Well guess what? We got fires burning fossil fuels and all our gasoline engines and power plants so that decreasing oxygen is just a reflection of the same thing that's causing CO2 build up, but it provides additional diagnostic information.

HOT GLOBE: Explain why fossil fuels, from your point of view and from your measurements, are really the overarching cause of what's going on with the curve, with increasing CO2.

KEELING: Well, it's pretty simple. And some people say, how do you know the buildup is caused by fossil fuel burning, not caused by something else. I should point out that historically, that question was never really. Viewed as needing even to be answered because it was. There was another question came to mind immediately when my father had these first measurements. And that is, you could see how fast it was building up, and you could do the math on how fast you expected it to be building up based on the rates that humans were using and burning fossil fuel. And what you found was that the buildup was slower than the amount we were adding to the atmosphere. So it proved that carbon dioxide was going elsewhere. So the question was always, where is this carbon dioxide that's not building up into the atmosphere going to? So the answer it's more than enough CO2 being emitted from fossil fuel to account for it. You could you could make an analogy. Let's let's suppose you have a chicken coop.

HOT GLOBE: Right?

KEELING: And on day one you put ten chickens in it and then you come back on day two and there are five chickens in it. What's the question.

HOT GLOBE: That's going to hurt the egg price!

KEELING: But what's the question? The question is what happened to the five chickens that disappeared? Right. So that was always the question with CO2. What's happening to the CO2 that's not ending up in the atmosphere?

HOT GLOBE: Possibly the ocean, possibly the land. What do you think?

KEELING: Yeah, exactly. Exactly. That was that was the issue. Of course, you can say that this fingerprint with CO2 going up and oxygen going down is also consistent with it being fossil fuel burning. There's isotopic changes that are also consistent with that. But the overwhelming simple reason that we don't worry about that is because we know how much fossil fuel we're burning, and we're burning a lot. We're dumping CO2 in the atmosphere in massive amounts, and it's not all staying there. Some of it's spreading elsewhere. That's what's going on.

HOT GLOBE: People talk about 1.5C and please translate that into Fahrenheit or 2 C. Are we blowing past that? How dangerous is the situation right now?

KEELING: Well, you're asking me to do the math on what 1.5 C is is. But it's probably two and a half or so or two. Two point something degrees Fahrenheit. Um, so, uh, these numbers, uh, came about from the application of, uh, the science to try to inform how to stay within dangerous limits for the Earth. Um, so this goes back to the framework convention to the with the goal of avoiding dangerous interference in the climate system. What is dangerous? Well, one measure of danger was that you don't go above some temperature threshold. Schultz, and they originally set a threshold of two degrees C, is that that's where it got dangerous. And then people realized, oh, that's a little bit deep into climate change.

There are particularly countries like the low lying Pacific island states that were going to completely flood it out in a two degree C world. So they didn't like that. Why aren't we trying for something a little more ambitious? So then they moved the target to to Aspirationally also be 1.5.

The problem is we're basically already at 1.5 and we're blowing right past it. And CO2 is rising faster than ever in the atmosphere. It's not just at the highest levels, it's rising faster than ever. So it's really hard to imagine that we're going to put on the brakes fast enough to even stop by 2 degrees C.

Not that we shouldn't try, but it's going to be a pretty hard target to hit given all the investment we have already in fossil fuel related infrastructure in our society that fuels our power sector and our transportation sector and so forth. So it's going to be very hard to move to renewables fast enough. Again, not that we shouldn't try.

So but I think more realistically we're heading towards about three degrees C now.

HOT GLOBE: Three degrees. What does that mean in Fahrenheit? And what would that mean in terms of fires, drought, floods and all the rest of the Four Horsemen of the apocalypse?

KEELING: Okay. Let's see. So 9/5 of three is 27 divided by five. So that's about a little over five degrees C. If I did the math right. I should say five degrees Fahrenheit.

HOT GLOBE: I should say that you did get your PhD at Harvard and we both went to Yale.

KEELING: But you're asking me to do math in my head. I hope I did it right.

HOT GLOBE: You did? All right. Go ahead.

KEELING: Sorry. Okay. So, um. Yeah, I mean, that's it's hard to put these even whether it's it's 5 or 3 degrees C or Fahrenheit or Celsius, it's still a little abstract. But these are huge changes in climate and, uh, that affect all sorts of aspects of the world around us and what's safe and what's not safe and where to live. And, um, so, I mean, the the last ice, to put it in perspective, the last ice age. Yeah. We had massive ice sheets over the planet. The world was about five degrees C colder. So three degrees C warmer is almost an ice age equivalent temperature change with going in the other direction.

HOT GLOBE: Wow.

KEELING: So you can expect that in a three degree C world eventually the the major ice sheets are going to massively melt. Sea level is going to go up eventually, probably tens of meters. That's like like 30ft or so or more. It won't happen overnight. It might take a thousand years for that to happen. But as we've said in place, massive changes that are unstoppable. Unstoppable Pretty much. Um, unless you massively near the geoengineer the planet. To somehow preserve life, we need to build a refrigerator over the poles to keep the. I don't know how that's going to work.

HOT GLOBE: But let's say we're talking 2050 or or, um, at the end of the century, is there any modeling or your own opinion about where we're going there?

KEELING: Well, you know, I'm not in the details of the modeling. I'm a carbon person. So you're asking me a little outside of my my specialty here, but, I mean, one one way to think about this is, uh, think about risks today.

HOT GLOBE: Okay. Risks today.

KEELING: I mean, let's suppose you live in a place that's prone to wildfires. How do you know how bad even a wildfire in the next couple of years could be? What's the basis for assessing that? Well, we don't have a history going back decades and decades to know what a 50 year fire looks like, because we're not living in the climate 50 years ago. So in order to even order to assess fire risk today or flood risk or any risk, you need a model to tell you how far we've moved off normal so you can predict extreme events like we've never had before. Um, so we're already living in a world that's heavily changed, and you can see it in what's happening to insurance rates, because the insurance companies can't just afford to assume the risks are the same as the past, they have to make inferences about new levels of risk.

HOT GLOBE: What does NOAA do that's so important for America, for Americans and for humanity?

KEELING: Well, I mean, NOAA does a number of things. And of course, they the weather forecasts.

HOT GLOBE: Weather forecasts are important to everybody.

KEELING: They also do things like looking after fisheries and some other related things like that. But they also have a research division called the office of the Ocean and Atmospheric Research. And this is basically fueling research to improve all aspects of weather forecasting and other things. So it's the research arm, but they're also the research arm is also doing quite an important suite of long term observations of the oceans and the atmosphere and so forth, that help us understand what's coming in the future. And for example, um, get back to this fire risk question. How do you know what the fire risks are today? Well, you need a model that's telling you how the climate's responded already to the increases in CO2 in the atmosphere.

So you need to understand what's happening with CO2 to even understand today's fire risks.

Um, and so the Office of Ocean and Atmospheric Research, one of the things they're doing is they're in partnership with us here at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. They're measuring the build up of greenhouse gases and related species in the atmosphere that track changes in the large scale composition in order to basically ground the understanding of how the system is changing. They also they're supporting measurements of ocean temperature at the surface and throughout depth. They have observing systems that look at changes in coastal areas that affect everything from fisheries to pollution, dispersion and so forth. The society really builds on these resources from NOAA to advance businesses and make assessments of risk and handle emergencies. Um, and a large fraction of this nationally is coming through this o.R. Office, which is which is potentially the office of Ocean and Atmospheric Research at NOAA. Um, so it's really it's a really important part of their enterprise and one that's now especially at risk.

HOT GLOBE: Especially at risk. I mean, is there any rational reason to put this at risk? Would anybody want to do that for a reason?

KEELING: Well, I mean, the latest pushback from the Or what is it called, path back from the Office of Management and Budget from the White House is naming has listed OER as something that should be substantially downsized and probably I don't know the exact language, but they were going to divide up some portion of it and put it elsewhere. But the the important point is that, you know what what what this office does is, is not, is relevant throughout society,

whether you're on one side of the aisle or the other side of the aisle, you need to worry about actual risks to things that you're doing, making investments long term, insurance companies, businesses, agriculture. What trees do you plant? How much, how much of the forest is going to grow? Um, these are basically economically important sources of information that depend on understanding how the climate is changing.

HOT GLOBE: All right. So it seems like crazy to mess with something that important.

KEELING: I guess I'd also say that, you know, the US really has led in this in the past, and what's basically underpinned our prosperity and our stature in the world in the last few decades is the US investment in science in general and our investment in,

in the climate, the science of climate and weather and environmental change puts us also in the forefront of understanding these things. So we have been leaders. We're a magnet for talent or have been and that's that's served us well.—Charles David Keeling

HOT GLOBE: Right. You know, switching off just a little bit. So fossil fuels are much more important than, say, reforestation. You know, you actually have the figures on where the CO2 is coming from? Talk for just a second about why forests are not necessarily the carbon sink they could be.

KEELING: Yeah, well, I think it's the. So this is really on the question of what could one do to bend the CO2 curve so that it doesn't go up more. And the main thing driving it up overwhelming cause is fossil fuel burning. And so it's going to be very hard to significantly bend the curve without reducing emissions of fossil fuel CO2. And that means moving over to more efficient technologies and fueling it with renewable sort of wind and solar. Um, this is something that people have heard a lot, but it bears emphasis that there's so much fossil fuel being burnt that's going to be hard to move away and reduce the curve without getting off fossil fuels. Now, at the same time, Um, people are talking about enhancing the sinks. Remember I said that not all the CO2 is actually staying in the air? Some of it's going elsewhere. Why don't we just improve, increase the sink uptake, and that will help offset fossil fuel emissions. Um, and so there's talks about various technologies for removing CO2 in the air, which could be viewed as a kind of a sinks enhancement technology project or goal. And among them is growing more forests or reforestation or afforestation. And, uh, those kinds of natural sinks have been much discussed. And they do have a role to play because they do take CO2 out of the air. So don't get me wrong. Yeah. Um, on the other hand, it's hard to imagine that they're going to scale up to be more than a small fraction of what we're emitting in fossil fuels. I mean, one way to look at it is that, you know, how much how much vegetation. If you look at all the carbon in vegetation around the planet, it's trees, including their roots and grasses and shrubs. You took all that, and let's suppose you burn it.

HOT GLOBE: Okay.

KEELING: How would that compare to the amount of fossil fuel we burned so far?

HOT GLOBE: If you burned all the green? Okay.

KEELING: Any idea?

HOT GLOBE: Uh, 10%.

KEELING: Well, yeah, it's in that direction. It's. It's more. Well, the point is that we've burnt so much fossil fuel that it's approaching, or maybe probably even surpassing the scale of all the vegetation on the planet. And the only way, the only way vegetation takes carbon out of the atmosphere is by putting carbon as biomass somewhere else. And what I'm saying is that the Earth didn't have to offset the fossil fuel emissions so far. By growing more forests and stuff, you'd have to double the amount of biomass in living living biomatter on the earth. Now there's more potential in soils. Soils hold a lot of Leftover detrital matter. Just organic compounds that are bound up with the soil. Um, so there's more potential in soil than there probably is in vegetation. But soils don't normally accumulate carbon very fast. And I should point out any of these sink processes that have carbon, you know, just hanging out there in the atmosphere, in the climate system or in the shallow layers of the soil are subject to disruption. So just because the tree is growing and flourishing today doesn't mean it's going to grow and flourish in the climate of 50 years. So you're not guaranteed to have a secure long term repository by putting it in a tree. Any tree anywhere is vulnerable to something happening to it, whether it's fire or pests or some kind of massive drought of a sort that the trees never endured in the past. So a better sink, in a way, if you can make the technology go, is to bury the carbon deeper in some reservoir or intervene in such a way that you're effectively titrating the carbon, reacting it away in a permanent way so that it's not part of the atmosphere pool anymore.

HOT GLOBE: Well, you know, how do you stay cheerful? Because these are pretty galling, uh, statistics that the perspective that you are very close to and understand, in fact, have given the world, yet, you know, do you go surfing? Do you have kids? You know, you seem to smile a lot.

KEELING: It's sort of a philosophical question. We all know that we're going to pass away at some point. And so you live. You try to live your life to the fullest with the highest purpose you can. And not not lose sight of the fact that there's years left to do some good on this planet while we're still here. So that applies also collectively to trying to to move the needle on this climate problem. So one one way I put it is that as much as we've come up short in a big way to mitigate the climate problem so far, the buildup of CO2 and so forth, it's still the case that the best time to intervene is now. So I often say there's there's there's no punting.

HOT GLOBE: No punting.

KEELING: Like in football. Yeah. So what does it mean to punt in football? Well, it means that you're, you know, you're kicking the ball downfield because you got to the fourth down and you couldn't carry. You couldn't carry the ball any further from the moment. But the assumption is that you're going to get the ball back and be able to carry it again in the future.

But there's no punting on climate. We can't kick this climate problem down the road and come back to a point that's equivalent to now. We always have to go for the fourth down every time around.

HOT GLOBE: Okay. Well, let's go for the fourth down, I like that. Well thanks, Ralph.

For Further Details on the Administration’s Assault on Climate and Weather Research, Science, and Reality:

SCIENCE: Trump seeks to end climate research at premier U.S. climate agency

White House aims to end NOAA’s research office; NASA also targeted

11 Apr 2025

11:18 AM ET

President Donald Trump’s administration is seeking to end nearly all of the climate research conducted by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA), one of the country’s premier climate science agencies, according to an internal budget document seen by Science. The document indicates the White House is ready to ask Congress to eliminate NOAA’s climate research centers and cut hundreds of federal and academic climate scientists who track and study human-driven global warming. . . .

If approved by Congress, the plan would represent a huge blow to efforts to understand climate change, says Craig McLean, OAR’s longtime director who retired in 2022. “It wouldn’t just gut it. It would shut it down.” Scientifically, he adds, obliterating OAR would send the United States back to the 1950s—all because the Trump administration doesn’t like the answers to scientific questions NOAA has been studying for a half-century, according to McLean.

LOS ANGELES TIMES

“The scientific backbone and workforce needed to keep weather forecasts, alerts, and warnings accurate and effective will be drastically undercut, with unknown — yet almost certainly disastrous — consequences for public safety and economic health,” the American Meteorologist Society and the National Weather Association said in a joint statement.

SEE HEROES OF SCIENCE--KEEPING CLIMATE RECORDS GOING AS TRUMP'S TROGLODYTE'S CUT FUNDING--

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/02/climate/national-climate-assessment-trump.html

Two Scientific Groups Say They’ll Keep Working on U.S. Climate Assessment

The organizations said they would publish researchers’ work even after the Trump administration decision to dismiss all authors on the project.

A person holding a balloon aloft on the top of a mountain.

A National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration technician collecting air samples on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, in 2023.Credit...Erin Schaff/The New York Times

https://www.wsj.com/science/environment/trump-national-climate-assessment-scientists-7c6b565b?mod=hp_lista_pos2

From the Wall Street Journal, 4/29/25

The decision Monday affected hundreds of researchers, scientists and experts who were contributing to the report, according to the authors. The most recent version, released in November 2023, found that extreme weather events cost the U.S. economy nearly $150 billion each year and disproportionately hurt poor and disadvantaged communities.

The assessment is used by state officials, emergency planners and businesses to prepare for extreme weather events in the coming years. Along with risks, it also outlines ways to adapt to a warming climate, such as changing farming practices, upgrading infrastructure to handle more rainfall and relocating homes and businesses from flood-prone areas.

“People around the nation rely on the NCA to understand how climate change is impacting their daily lives already and what to expect in the future,” said Rachel Cleetus, a senior policy director at the Union of Concerned Scientists and an author of the report. “Trying to bury this report won’t alter the scientific facts one bit, but without this information our country risks flying blind into a world made more dangerous by human-caused climate change.”

The National Climate Assessment has been mandated under law since 1990 and is developed by the U.S. Global Change Research Program, the federal unit that Congress created to organize the reports. The assessments are produced in a yearslong process by contributors and reviewed by federal agencies.

The federal government released its fourth National Climate Assessment in 2018 under Trump’s first administration. The report detailed the effects of global climate change, if left unchecked, and how efforts to slow the effects of rising temperatures were falling short. President Trump at the time said he didn’t believe the report’s assessment that global climate change would cost the U.S. billions of dollars in economic losses each year by the end of the century.