HOT GLOBE TALKS BIODIVERSITY, COVID & WRITING WITH DAVID QUAMMEN

The Most Likely Origin of Covid Dictates A New and Respectful Relation to Our Fellow Creatures Because Nature Doesn't Exactly Bite Back--Exactly

HOT GLOBE here, speaking with David Quammen, author of the book BREATHLESS: The Scientific Race to Beat a Deadly Virus, that virus being, of course, COVID. David, has nature come back to bite us?

DAVID QUAMMEN: It's good to be with you, Steve. Good to have a chance to chat. We're years overdue. Couple of fellow Montanans, working stiffs, freelance writers.

Has nature come back to bite us? I am wary of that particular metaphor because it tends to personalize nature. I am a black hole Darwinian materialist, not a mystic kind of guy. What we're seeing is all about ecology and evolutionary biology, and, yes, this is a consequence of things that we are doing. It's part of a larger pattern, almost certainly a virus that came from a horseshoe bat through an intermediate animal and spilled over into humans, although as you well know there is still a ruckus of controversy over the origins question.

“Some people prefer the notion of a lab leak but I don't see any evidence for lab leak, and I see lots of historical and scientific evidence for natural origins.”

That said I'm writing a piece about that subject myself and I am making a point to listen to some of the more intelligent and rational lab leak people who can't yet be ruled out. But the principle of parsimony and the empirical evidence that exists points me and a lot of others in the direction of natural origins, nature biting us back in a sense.

HOT GLOBE: OK, one of the most brilliant and fun things about the book is that it reads like a—I hate to say it—breathless page turner from the beginning, detailing the origins that Americans--being Americans--have already begun to forget.

QUAMMEN: I give a not quite minute-by-minute, hour-by-hour, day-by-day account of the first cluster of infections being detected in Wuhan and the first news of that getting out to the world and the first news that this seems to be a coronavirus causing these infections and then the first publication of the genome of the coronavirus so that people like Tony Fauci and Barney Graham at the Vaccine Research Center could grab that genome and start working on vaccines. I tell that story in the voices of the people that I interviewed through the perspectives of the people who were involved and I tried to make it a rattling good narrative as well as a scientific explanation.

HOT GLOBE: Your personal arc has been fascinating and strangely consistent.

QUAMMEN: It has been a journey that unfolded for me triggered by circumstance and opportunity and the need to make a living and following what interested me most. I went from being a fiction writer having published three novels and a book of short fiction. I turned into a nonfiction writer for magazines focused first on natural history but then quickly on biological sciences, evolutionary biology, ecology, conservation, a lot of conservation biology, and in 1996 I did The Song of the Dodo, big ambitious book about evolution and extinction on planet earth, and then in 1999 I was doing a project for National Geographic that involved walking across long stretches of Congo forest with a wonderfully crazed, dedicated, hard-bitten American ecologist and conservationist named Mike Fay, a project that he labeled “the mega transect,” three stories in National Geographic. I followed him for weeks and weeks slogging through the Congo forest.

HOT GLOBE: Slogging is an understatement.

QUAMMEN: Yeah, it was tough travel. It was fascinating. It was a great opportunity. We were walking off trail, bushwhacking with a small crew that he had recruited of, originally, Congolese and then Gabonese fellows, and you're slogging through swamps, crossing blackwater rivers, all this in river sandals and river shorts and in the course of that we spent ten days walking through what was known as Ebola habitat. The reservoir host, the animal in which Ebola virus hides, lives over long periods of time when it's not spilling over into humans and causing infections. It has to have a reservoir host. That animal was unidentified. We knew it was there somewhere in the forest. We didn't know which animal it was but in the course of doing that and writing about that I got very interested in scary viruses, Ebola first and then the whole subject of viruses that can emerge from wild animals and infect humans and sometimes cause epidemics or pandemics, and that's what led me to Spillover, to The Chimp and the River about the ecological origins of HIV, the AIDS virus, and then eventually to this COVID virus, SARS-CoV-2 and its story, and it really is the main character of my book Breathless, a book about the origins and evolution of that virus and its fierce journey through the human population.

HOT GLOBE: Is another pandemic coming and what sort of approaches should we employ to stop it?

QUAMMEN: That's an important and huge question. There are more pandemic threats coming. We live in a world of viruses. Every species of animal, plant, fungi or bacteria on this planet has its own viruses. The ones that live in animals, particularly mammals, have the potential to become human infections. Also, some bird viruses have the capacity to become human infections.

HOT GLOBE: Very scary, bird flu.

QUAMMEN: All of the influenzas that infect humans come from wild aquatic birds, so there are influenzas lurking out there that could become pandemics for us. There's a whole group of viruses called the RNA viruses. They have RNA genomes instead of DNA genomes, right? And they mutate more frequently. Therefore, they're capable of switching hosts more easily than other kinds of viruses.

The first AIDS virus probably came from a single chimpanzee right in the southeastern corner of Cameroon that was probably hunted, killed and butchered by a human who got blood-to-blood contact. It's called the cut-hunter hypothesis. We don't know who was the real Patient Zero but the likely inference is that it was a human who got chimpanzee blood into a cut on his or her, but probably his, hand or arm or back and became infected with this chimpanzee virus that became HIV.

HOT GLOBE: You’ve probably thought a bit about how humans could react better with our fellow species?

QUAMMEN: Well, absolutely, I mean we both used the phrase “messing with these animals” but the exploitation of wild animals for food and the disruption of highly diverse ecosystems, especially tropical ecosystems, because they are the most diverse, in the course of the things that we humans do, brings us into contact and exposes us to the viruses that wild animals carry, and that means capturing animals to ship them elsewhere for food, killing them, butchering them, but also logging, mining, building timber camps, building mining camps in tropical forests which tends to lead to workers living on what we call bushmeat.

“Bushmeat is a term that we apply to poor people in Africa exploiting wildlife. In Montana as you know we call it game! It's really not a distinction except semantically.”

HOT GLOBE: Would you be a proponent of the “Half Earth” concept?

QUAMMEN: We have to reduce our footprint on the wild ecosystems for our own sake as well as for the sake of biological diversity on planet Earth. “Half Earth,” of course, is a concept famously proposed by [Harvard biologist and Pulitzer Prize author] Edward O. Wilson, the great Ed Wilson, who I was privileged to be a friend of, and a reader of his and someone influenced by him. We lost him about two years ago. He proposed that half of the Earth's surface be set aside for nature. That's an ideal and he believed in challenging people with ideals. I don't know how you get there but the basic principle is we need to be less disruptive of the wild ecosystems that remain. Leave them alone as much as we can, and that means somehow reducing the combined impact of human population numbers multiplied by human consumption, not just human population numbers because most of the humans on planet earth don't consume very much. The minority of us affluent people living in affluent countries do most of the consuming so the combined impact of human population size and our consumption--you know, you and I are privileged to consume ten times as much as the average family of five in a village in southeastern Cameroon--so when we're talking about game or bushmeat, you've got to figure out a way to give people a real living without having to resort to that, and that brings us in a way to Gorongosa National Park [in Mozambique] something that we've been hearing about at the Society for Environmental Journalists conference that you and I are attending today [in Boise, Idaho.]

Gorongosa embodies all of the most sensible ideas in conservation, which is you protect a wild ecosystem but not by locking the local people out and leaving them to their own devices. It's a national park restoration project that is founded on ideas of human rights as well as biological diversity. It was conceived and has been financially supported by a wonderfully big-hearted imaginative fellow named Greg Carr and his principle from the beginning was we want this national park to be the best thing that has ever happened to the 100,000 people living in villages surrounding the park in the buffer zone. We want it to be good for them. We want to bring education to their children. We want to bring healthcare. We want to bring alternative sources of revenue such as shade-grown coffee being grown on Mt. Gorongosa in native tree forests that have been restored by the labor of these people and marketing it and making a decent living.

At dinner last night I sat next to a fellow named Shannon Wheeler, who is deputy chairman of the Nez Perce tribe here in Idaho. We talked about this a little bit, the things that were being done with the local people who had surrendered part of their territory to the park, and then I turned to Shannon and said, well you know, you know about this more painfully than any of us because it happened on the American landscape and there haven't been projects such as Gorongosa that have worked with the people here. We crowded them onto reservations. We violated our treaties, you know, we packed them into places where they struggled to make a living. He's a wise fellow and he nodded very knowingly and talked a little bit about that, but, yeah, it happened everywhere.

The great, horrible story of the Nez Perce being pursued by the US cavalry and through Yellowstone park and through the Big Hole Valley of Montana, finally up to the Bear Paw Battlefield in northern Montana. A great teacher and writer who was my mentor beginning in college, a man named Robert Penn Warren, wrote a poem entitled “Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce.” I was living in Montana by that time and he called me up one day and said, “David, I've been working on this poem about Chief Joseph for 40 years. I want to come out and see the Bear Paw Battlefield. Would you go up there with me?” So I picked him up at the Great Falls airport in my little yellow Honda and we drove up to the battlefield and walked across it and he knew all the history and he saw the different graves and knew the warriors that had died there, and then he went back to Connecticut and Yale and wrote this poem, “Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce” about the tragedy of what had happened to a peace loving man, the great Chief Joseph. I believe it was he who said, “From where the sun now sets, I will fight no more forever.”

HOT GLOBE: Robert Penn Warren also wrote the famous novel All the Kings Men, about the Louisiana politician, Huey Long. Did you meet him at Yale?

QUAMMEN: I showed up there in ‘66 from Cincinnati. I went to Yale because a Jesuit teacher that I had, had told me you should consider Yale, don't just think about Jesuit colleges, think about Yale. Well, why Yale, father? “Well they've got the best English department in the country.” What's so great about their English department, father? “Well, they've got Penn Warren for starters, Robert Penn Warren.” Who's Robert Penn Warren, father? “Well, he co-authored your textbook on understanding fiction but he's also a great American poet, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist of All the Kings Men.” Oh really? And so I went to Yale and three years later I found myself under the wing of Robert Penn Warren.

Warren was a huge personal influence. He was a great friend to me. He helped me get my first book published. He helped me get a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford. He asked me one day, “Are you going to apply for a Rhodes scholarship?” What's that? “Well, it's two years at Oxford.” Well, I don't want to spend two years studying at Oxford, Mr. Warren. I want to be a writer like you. And he came out of his chair almost, I can remember, and said, “Well, of course you don't want to spend two years studying at Oxford! But you'll be three hours from Paris, man!” So he wrote a recommendation and next thing I knew I was three hours from Paris, at Oxford.

HOT GLOBE: I was amazed you didn't leave your house in Bozeman for two years during covid, a wonderful house, I should add, that resembles the British Museum only somewhat smaller. What’s next?

(A wall of Quammen’s house in Bozeman, Montana.)

QUAMMEN: Right now I'm working on a piece for the New York Times magazine on the issue of the origins of the virus and the debate around it.

I have a new book coming out May 16 from National Geographic Press, based on conservation stories that I've written over the course of 20 years, titled The Heartbeat of the Wild. It's really my vision of what works and what doesn't work in conservation of biological diversity in the 21st century.

HOT GLOBE: Why do you think Americans, especially, forgot that the 1918 flu killed essentially the same number of people, 600,000, as covid, though mostly young and fit men, the opposite of the gutting of older people and the overweight today. We made covid political and then that was that. What's wrong with this country?

QUAMMEN: Well, it's not just us. It's the world. The world wants to forget disasters. The world worked hard to forget the 1918-1920 influenza catastrophe which killed about 50 million people around the world.

But there's a lot we can do about the catastrophic losses of biological diversity, the things that we eight billion humans do as we consume resources, as though everything on the planet simply exists for our pleasure and use. That ranges from meat being harvested in the forested areas of Africa to the uses that we in high- income countries make of the minerals cobalt and coltan for the smartphones such as the one on which you're recording this interview and the one in my pocket and our laptops and the hybrid or fully electric cars that we drive, all of which use batteries that require cobalt.

HOT GLOBE: Are you arguing strongly for a reappraisal of how humans should live?

QUAMMEN: Yeah, a reappraisal. A rethinking of what we need and how much we need to consume and where it comes from and, of course, the reason cobalt is a concern is because it is mined in just a few places including the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, where men women and children are going into open pit mines and down into shaft mines digging cobalt out with their hands and dying in shaft collapses and making miserable small wages when they don't die and presumably feeding themselves when they need protein with bushmeat, which exposes them to diseases as well as death by cave in. And they're doing it in order to supply us with cobalt for the batteries in our smartphones, our laptops and our cars. I mean, everything is connected not only in the ecological sense but in the way that we interact with the world.

HOT GLOBE: I didn't think we'd get around to cobalt but it's all connected. “Ecstasy is intimacy with all things,” I think that's a 13th century line, with a more positive spin!

QUAMMEN: That's good.

HOT GLOBE: Dave, I don't think we'll forget COVID after we read your book.

QUAMMEN: Thank you. It's a terrible subject but I hope the book reads like a guilty pleasure.

HOT GLOBE: Let's end on guilty pleasures, then.

[laughter]

This interview was edited for length and clarity. Expect the full audio podcast in several days.

David Quammen at home with Hot Globe’s Steve Chapple.

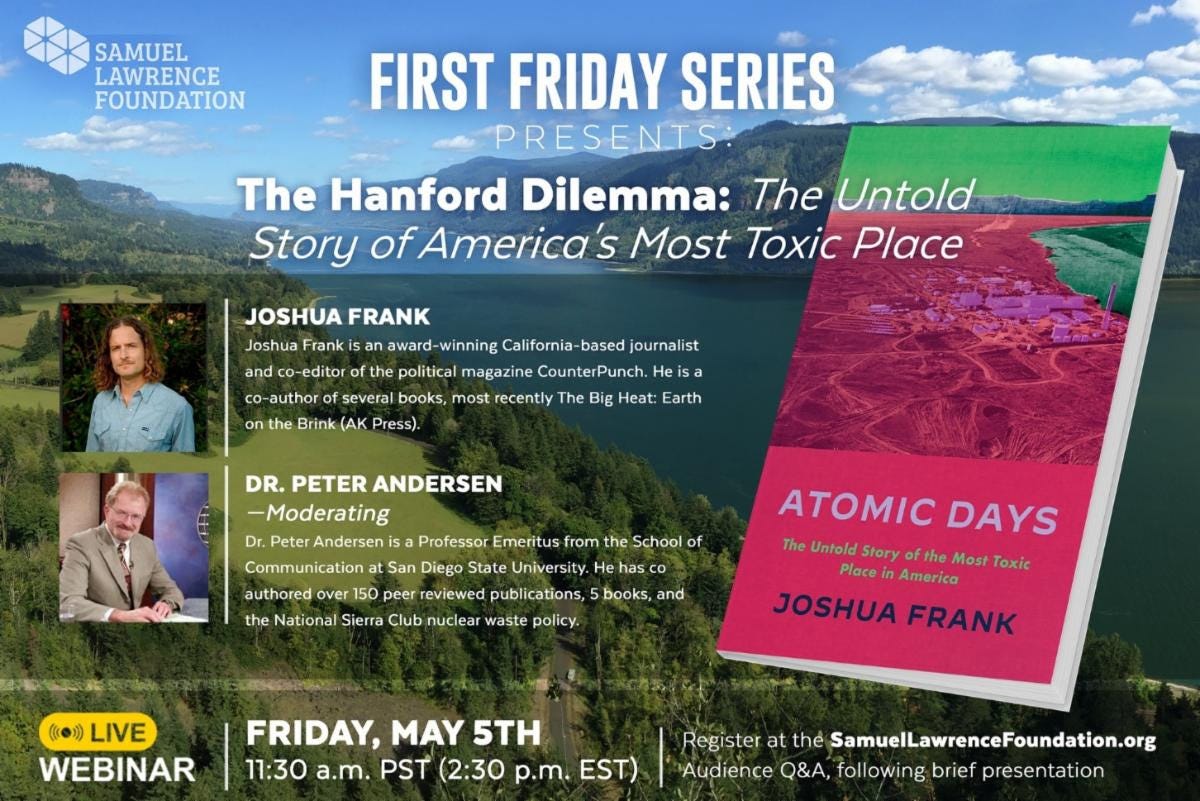

And Don’t Forget, our Partner, the Samuel Lawrence Foundation, hosts its “First Friday of the Month” Webinar today May 5, 2023:

Really excellent article by Quammen in today’s NY Times Magazine on the origins of Covid. Take a read. It’s the best sum-up yet, and also revisit HOT GLOBE’s April column with Dave and a fascinating Audio a week later. DQ’s literary touches come through nicely:

We still don’t know how the pandemic started. Here's what we do know — and why it matters.

By David Quammen

David Quammen is the author of “Breathless: The Scientific Race to Defeat a Deadly Virus,” about Covid-19, and “Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic,” among other books.

July 25, 2023Updated 10:28 a.m. ET

Where did it come from? More than three years into the pandemic and untold millions of people dead, that question about the Covid-19 coronavirus remains controversial and fraught, with facts sparkling amid a tangle of analyses and hypotheticals like Christmas lights strung on a dark, thorny tree. One school of thought holds that the virus, known to science as SARS-CoV-2, spilled into humans from a nonhuman animal, probably in the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, a messy emporium in Wuhan, China, brimming with fish, meats and wildlife on sale as food. Another school argues that the virus was laboratory-engineered to infect humans and cause them harm — a bioweapon — and was possibly devised in a “shadow project” sponsored by the People’s Liberation Army of China. A third school, more moderate than the second but also implicating laboratory work, suggests that the virus got into its first human victim by way of an accident at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (W.I.V.), a research complex on the eastern side of the city, maybe after well-meaning but reckless genetic manipulation that made it more dangerous to people.

Listen 58:14

apps.apple.com/us/app/nyt-audio/id15492…

If you feel confused by these possibilities, undecided, suspicious of overconfident assertions — or just tired of the whole subject of the pandemic and whatever little bug has caused it — be assured that you aren’t the only one.

Some contrarians say that it doesn’t matter, the source of the virus. What matters, they say, is how we cope with the catastrophe it has brought, the illness and death it continues to cause. Those contrarians are wrong. It does matter. Research priorities, pandemic preparedness around the world, health policies and public opinion toward science itself will be lastingly affected by the answer to the origin question — if we ever get a definitive answer. MORE —-

And see Dave Quammen's recent Op-Ed in the NY Times: "WHY ARE BIRDS FALLING FROM THE SKY?"--https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/23/opinion/bird-flu.html